If you don’t recognise Louise Beavers’ name, you’ll certainly recognise the type of roles that she played. Accepting the racial prejudices embedded into Hollywood films in the 1930s and 1940s, Beavers took the role that was always available to her: that of the quintessential ‘mammy’ figure. Yet for Beavers, playing to type didn’t mean fading into the background. Her not inconsiderable talent allowed her to imbue each role with subtlety and a certain dignity, forcing audiences to acknowledge her characters despite the stereotype. That elevation was in part aided by Beavers’ own personality; she was, by many accounts, not exactly the ‘subservient’ figure those screen roles suggested.

Beavers is probably best known for her role as Delilah Johnson in John M. Stahl’s Imitation of Life (1934) – indeed it was the film that transformed her from a ‘shadow’ actress into a star in her own right. For many critics, Beavers’ role as Delilah eclipsed Claudette Colbert’s lead; the fact that it didn’t lead to an Academy Award nomination was seen by many as a racial snub (that took until 1940 to be rectified, when Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win for her role in Gone With the Wind). Columnist Jimmy Fiddler wrote:

“I also lament the fact that the motion picture industry has not set aside racial prejudice in naming actresses. I don’t see how it is possible to overlook the magnificent portrayal of the Negro actress, Louise Beavers, who played the mother in Imitation of Life. If the industry chooses to ignore Miss Beavers’ performance, please let this reporter, born and bred in the South, tender a special award of praise to Louise Beavers for the finest performance of 1934.”

Much Imitation of Life conforms to the racial stereotypes of the era and defines what ‘blackness’ meant in America in the 1930s. Widowed Bea Pullman (Colbert) manages to elevate the position of herself and housekeeper Delilah by selling the latter’s ‘secret pancake recipe as the perfect complement to the maple syrup business her own husband had built up. And whilst the two women share a real bond – not just the result of the businesses partnership but also because both are single mothers looking to make a better life for their daughters – differences remain. Success should liberate both Bea and Delilah, but the housekeeper prefers their roles to remain the same. She wants to remain Bea’s paid help. She doesn’t hanker after her own house or an independent life. The subservience reaches a pinnacle when she rejects an offer to own 20% of the pancake company she helped to establish (although probably less than deserved an unusual offer), deciding instead that it’s more important to continue working for her white ‘family’. By making her self-worth dependent on her owners, she reinforces the idea that she herself has little or no value, everything she can offer must be see through the lens of ‘whiteness’.

One counterpoint to this subservience is her daughter Peola (played by Fredi Washington). The lighter-skinned Peola wants to belong in the white world, but her darker-skinned mother always thwarts her efforts. But why should she embrace her blackness? If her mother is taken as the benchmark, that means a life that relies on whites to be validated, a life of dependence rather than independence. Peola’s character is really there to ask questions that it was impossible for Delilah to ask herself. Beavers’ whole role – and prominence in the film in general – relies on the cheery disposition for which she was famed. An audience wouldn’t have been receptive – or sympathetic – towards an angry Delilah, no matter how justified. But fully embracing the Mammy ‘type’ (and it was particularly ironic considering how much the actress detested kitchen work and particularly hated pancakes and waffles) allowed another actress – in this case Washington – to challenge it and, in truth, created more empathy for Delilah, who gives so much but gets little of value in return.

In truth, Louise Beavers’ influence extends far beyond one film. Imitation of Life might be her best-known role, but it had repercussions for the rest of her career. The fact that she was able to hold her own against ‘white’ actresses hardly endeared her to be considered for other lead roles. And her obvious talent meant that her salary demands were often above the going rate for the type of roles open to her. And whilst it’s now impossible to imagine but Hattie McDaniel in the role of Mammy in Gone with the Wind, surely at the time Beavers would have been the natural choice (granted, it would have been a very different role if Beavers had taken it!). That oversight must’ve felt like a snub.

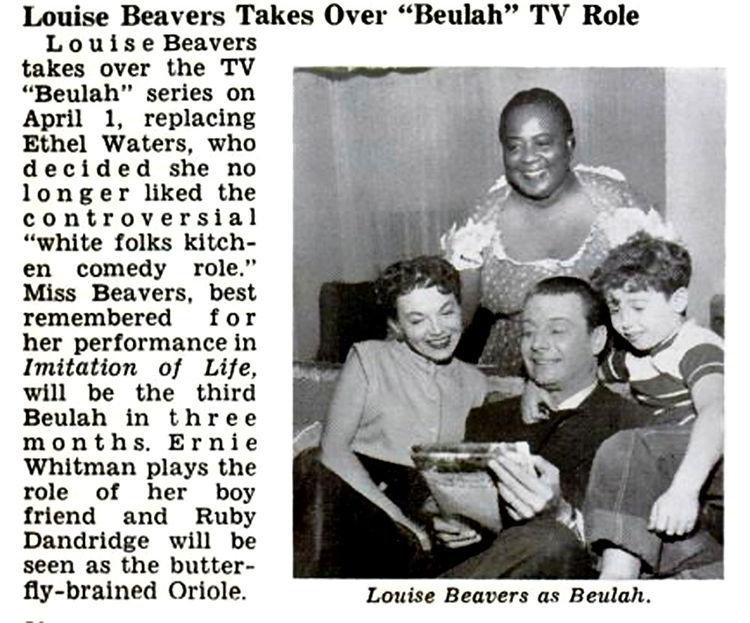

After Hollywood, Beavers did go on to successful TV career. In a particularly ironic twist, she replaced Hattie McDaniel in the lead role of Beulah, a TV comedy that centred on a domestic and her white employees. Interestingly, when the show first aired on radio, Marlin Hurt, a white actor, played the character. When it rebranded as The Beulah Show in the late 1940s, Hattie McDaniel replaced the (still male) lead, in the process doubling the ratings. It was the first time a black woman had been billed as the ‘star’ of a network radio program. The problems began when the show was adapted for TV, first with Ethel Waters in the lead and later Daniels and Beaver. Very few episodes survive; what does confirms the criticisms of the day – mostly that the black ‘mammy’ character reinforced racial stereotypes and embedded prejudices deeper into society.

On the surface, Beulah was the perfect role for Beavers. It was the sort of characters she played well. It was the type of character audiences expected her to play. But playing to type was damaging, and helped create a one-note legacy that overshadows much of Beavers’ other achievements. Viewing Beavers’ achievements through the lens of her two most famous roles is also detrimental because they don’t capture the nuances of Beavers the woman. Off-screen she was far from subservient and fought against many of the popular caricatures associated with African Americans. In response to Delilah Johnson’s decision not to take a stake in the business when offered, Beavers commented: “Let somebody walk up to me now and ask if I wanted $20,000 – I’d take it and ask what for… I am playing the parts, I don’t live them”.

Beavers understood that the only way to challenge the system was to play the Hollywood game well. But her talent was her undoing – she was too good at playing the roles she was ‘meant’ to and was never able to advance beyond them. That might seem like a failure. But by playing type so well, and being penalised for it, she initiated a wider discourse on race and what ‘blackness’ meant and, in doing so, was able to create new representations for the actors and actresses who followed her.

Sources: African American Actresses: the struggle for visibility, 1900 – 1960 by Charlene B. Regester / Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams: the story of Black Hollywood by Donald Bogle

This post is part of the What A Character! Blogathon 2015, from the hostesses with the most-est, Once Upon A Screen, Outspoken & Freckled and Paula’s Cinema Club. Read all the posts here!

Fascinating article. I often think of the dilemma African American actors faced in the studio era, between accepting the roles that were available and having to act out humiliating stereotypes. Not that Beavers ever stooped to Stepin Fetchit levels, but that “I live to serve my white mistress” bit is a pretty sad comment on what white audiences wanted to believe.

Ahhhh Louise! Not as caustic as Hattie McDaniel and loved seeing her in the movies. I’ll never forget her in “Bombshell” right at the top of the movie, she has to wake up Harlow’s assistant, the great Una Merkel. When Una chastises Louise about not getting up early enough to wear her uniform, I LOVED the forceful forthright way Louise looks her in the eye and tells her: “Don’t scald me with your hot water. I knows where the body’s buried!” Thanxx for spotlighting her!

I probably should think of “Imitation of Life” first when I think of Louise Beavers, but it trails behind “Holiday Inn” and “Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House”. This actress always gave better than she got.

Wonderful post. Beavers was softer than McDaniel, but every bit as talented. Good job all around.

What a marvelous article! I recently saw Imitation of Life and got angry at several moments – like when Delilah massages the feet of her partner. In so many scenes she diminishes herself, and it was a bit of what happened to Louise when playing the “mammy” type. But I’m glad she wasn’t as calm and naïve as the stereotype.

Thanks for the kind comment!

Kisses!

Le

Fascinating to read this. She made an amazing number of films, sad that stereotyped roles were so often all that was available – but she certainly pours her character and quality into the films, judging by those I’ve seen. I’ve only seen the Douglas Sirk remake of ‘Imitation of Life’ as the original isn’t available on DVD in the UK except on import, but I’ve now discovered that Universal is offering it for paid streaming via their UK Youtube channel, so I’ll hopefully be able to see it soon!

Great choice for this blogathon! Louise Beavers was indeed excellent in IMITATION OF LIFE and it’s a shame it didn’t lead to a more substantial film career. As for the Academy Awards, it’s amazing that the film industry is STILL dominated, in large part, by white males. You can’t be nominated for an Oscar if you don’t have an opportunity to compete for roles or direct films. Louise Beavers was a true pioneer, but many more roads remain to be paved.