Barbarella: Queen of the Galaxy is a conundrum. On first watch, it’s a camp sci-fi romp that exploits the talents of Jane Fonda, from the space suit striptease that accompanies the opening credits to the revealing costumes. But a second viewing suggests that, despite the trashy, soft-core stance, Barbarella is an empowered female astronaut who attracts (and is attracted to) both men and women and always (if you’ll pardon the pun) comes out on top. In terms of gender roles, it’s a movie with limitations but, considering the era in which it was made (the late 1960s), it’s surprisingly progressive. At the time, the male-led ‘space race’ was at the forefront of many cinemagoers’ minds; Barbarella was an alternative – a female astronaut who was sexy, single and political – a highly dangerous combination.

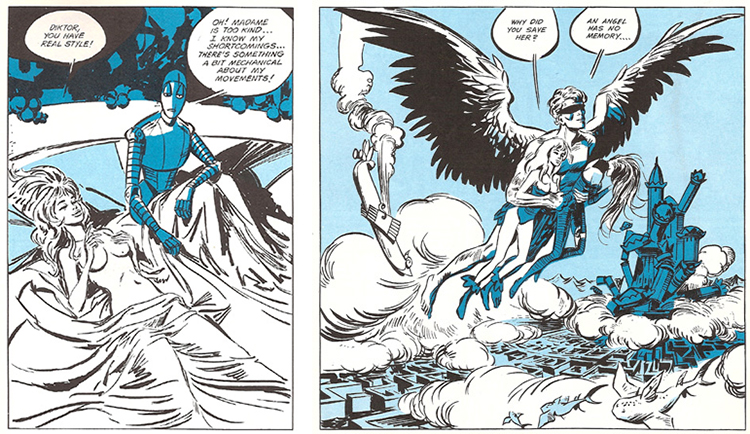

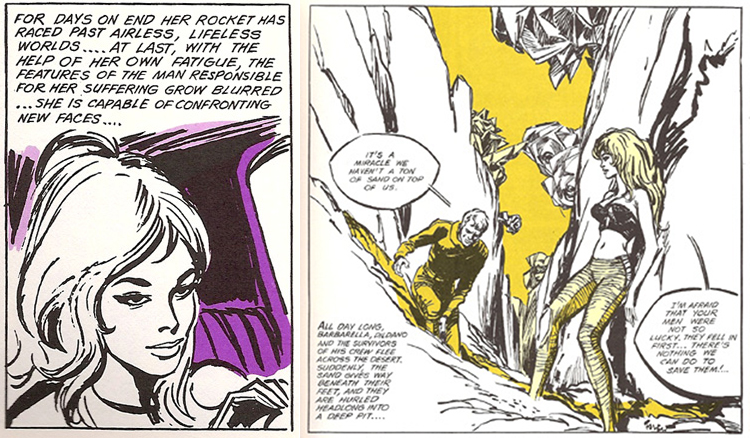

The film is based on a French comic strip, created by Jean-Claude Forest, and was directed by Fonda’s then husband, Roger Vadim. Forest introduced the character in V-Magazine in 1962, and in 1964, the strips were published in a standalone comic book; it’s supposedly X-rated content generated considerable controversy and it became known as the first ‘adult’ comic book. It seems even her contemporaries didn’t know how to take Barbarella. Written for the screen by Terry Southern (also responsible for Doctor Strangelove and Easy Rider), the film adaptation is a faithful homage to Forest’s creation

Both the film, with its wooden dialogue and shag pile sets, and Fonda’s wide-eyed performance are often criticised. It’s often regarded as one of Fonda’s worst performances and much of Barbarella errs on the side of ridicule – a nude meeting with space station commanders, mechanical dolls with razor-sharp teeth, an evil lesbian queen, and, of course, Barbarella’s ability to ‘sleep her way around the galaxy’. There is a lot of sex, and a lot of its very clichéd, but in the main, Barbarella retains control. She isn’t stripping for anyone apart from the camera in the opening credits; this is something she indulges in for herself. Her initial rejection of Mark Hand, who she meets when her ship crash-lands on Duran Duran (that’s a planet, not the band) is based on her practical Earth-bound experience of sex, which involves psychocardiograms, pills and hand holding. The flipside of control is torture, and Barbarella experiences this too, through actions that are designed to keep her in check. She’s attacked by vampire children, held captive in a glass dome filled with angry birds and placed in the Ultimate Chamber of Death. Each torture is designed to keep her in check and emphasise her vulnerability, but her survival instinct, coupled with her ability to read political and social situations, ensures she triumphs over her captors.

It’s likely that Barbarella seems more feminist today because of Jane Fonda’s image. Initially known as a sex symbol, she evolved to become – and indeed remains – one of Hollywood’s most identifiable and popular feminists. According to Fonda:

“Barbarella is a film that’s always brought up, but as a matter of fact, I was hardly ever nude. Most of the pictures where I was dressed to the teeth and played a cute little ingénue were more exploitative than the ones with nudity because they portrayed women as silly, as mindless, as motivated purely by sex in relation to men…”

She had previously described the film as ‘as kind of tongue in cheek satire against bourgeois morality’. For all its fantasy, Barbarella does introduce some interesting discussions around sex, empowerment and desire, but Vadim was more interested in playing for laughs than opening a discourse around gender. Considering that the media would likely have been filled with stories about sexual liberation and feminine identity, moviegoers might not have appreciated the director impeding on their escapism with a moral barometer. But Barbarella was never going to be a mainstream crowd-pleaser, it was already appealing to a niche audience and by opting for entertainment over enrichment so the opportunity probably was there. Instead, Vadim produced a film that’s more often ridiculed than praised.

Paco Rabanne’s skimpy, flesh-revealing costumes do little to further Barbarella’s status as feminist icon, but are in keeping with most of the other characters and the fetishist elements of the film. Bare-chested blind angel Pygar (played by John Phillip Law) and The Great Tyrant (Anita Pallenberg) are similarly (un)attired, in outfits that pay homage to ancient Rome through a futuristic lens. It’s the perfect blend of classic and futuristic, set off by toned bodies and bouncy 60s hair.

There’s very little information about how Rabanne became involved with the movie, but it’s likely that he met Vadim in Paris, where he opened a shop in 1966. Rabanne originally studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-arts in Paris, and then sold plastic buttons to some of the city’s largest couture houses, including Givenchy, Dior and Balenciaga. There, along with Pierre Cardin and André Courrèges, he began experimenting with futuristic fashions that incorporated alternative and experimental fabrics, inspired by space and space travel. His designs for Barbarella are a distillation of some of his most futuristic ideas. Fonda’s figure was the perfect blank canvas for moulded plastic crop tops, chain mail capes and mosaic-tile bodysuits; impractical, unwearable they encapsulate fashion from another galaxy. Over-the-knee silver boots with foldback cuffs reference pirates and travellers, highlight her adventurous spirit and the sheer fabrics of the (numerous) leotards and bodysuits tear and rip easily, allowing the audience to enjoy Fonda whilst appreciating the physicality that being an intergalactic traveller entails.

These so-called couture Space Age fashions dominated in Paris, but were slow to cross the Atlantic; American audiences would have been unfamiliar with the youthful aesthetic, adding to the futuristic elements of the film. Rudi Gernreich, a fashion designer based in California, was the sole purveyor of the look in the US, appeared on the cover of TIME in 1967, just before Barbarella was released. The fashion wasn’t really intended for mass market – many of the fabrics required couture-like techniques and were expensive and difficult to obtain. Interestingly, compared to the cluttered environs of Barbarella’s spaceship, Space Age fashion favoured minimalism: clean lines, structured silhouettes and limited colour palettes. Although Rabanne, Cardin and Courrèges remain household names, the result of successful fragrance launches and brand tie-ins, Space Age fashion was over by the late 1960s, replaced by flowing psychedelic hippies. Despite that, the designs remain a visual shorthand for the decade, and influence how we think about intergalactic space dress, as it becomes a real possibility for travellers.

Of course, dressing Barbarella in any other way would have undermined the blonde-bimbo, sexpot stereotype that Vadim was keen to create. But the fact that she (after getting over her psychocardiogram hang-ups) actually enjoys sex and does it for personal pleasure is interesting. Is it a comment on women’s sexual liberation, or a cheap joke to garner controversy? In truth, probably the latter, but viewing Barbarella from a contemporary angle, where female characters are still often expected to conform to male-dictated ideals of sexual desire, she starts to look almost progressive.

Further reading: Bringing Barbarella down to Earth: the astronaut and feminine sexualty in the 1960s by Lisa Parks / An interview with Jane Fondo by Roger Ebert

Outstanding article; I love the tie in with fashion and the historical analysis of Jane Fonda. 🙂

Thank you Cindy! Happy you enjoyed the post

An interesting discussion, I believe I’ve brought up this point before though not quite in as much detail. For the time period I would agree that Barabarella was actually fairly progressive in that she was a complex self-reliant and competent protagonist. Admittedly it would have been nice if she’d actually had a chance to participate in the final battle rather than remain trapped in the Queen’s chambers watching it on a screen but I guess there was only so much you could get away with then.

One way you could look at Barbarella, or at least how I’ve interpreted her, is that as oversexualized as she was the fact that she was written as a competent and determined individual who was able to think for herself and didn’t just submit to the will of men may have helped to create a path for other sci-fi heroines. This may sound crazy but I’ve suggested that Barbarella might have indirectly helped make it possible for characters like Ellen Ripley or Eleanor Arroway or even more recently Ryan Stone to have the impact that they did.

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. I didn’t mention it, but I am disappointed that Fonda didn’t feature more in the final scene, and had to be rescued by Pygar, it seemed to undermine a lot of the other, more progressive aspects. I don’t think it’s farfetched to draw a parallel between Barbarella and Ripley; I like to think if Barbarella had been made in the 80s she’d share more of her qualities.

Well, that’s just it. As disappointing as her lack of involvement in the climax may be by modern standards, Barbarella may have indirectly paved the way for someone like Ripley who ends up being the only one to make long enough to participate in the climax. If nothing else it’s one step in a gradual process.

Wow, great article. I’m still not sure how i feel about Barbarella and feminism. One person could see it as sexual empowerment while another could see it as just titillation at Fonda’s expense. However I suppose that confusion is part of the reason the film has survived so long and is still being discussed.

It’s almost like they’re both at the same time. I think her husband/ director took advantage of their relationship and talked her into things she wasn’t comfortable with. And if Fonda hadn’t become such a committed feminist later in her career there would probably be a lot less said about the angle.

I’ve been going through a lot of Fonda’s movies from the 70’s in preparation for a blogathon I expect to be announced soon for August, and I should give this another try for a contrast. The first time I was able to get through this, I didn’t see this as much more than, as Mikey B puts above, titillation at Fonda’s expense (I preferred the movie-within-a-movie parts of Roman Coppola’s CQ, which played as a combination of BARBARELLA and MODESTY BLAISE, but better than those movies turned out to be), but maybe a second viewing will change my mind.

Don’t get me wrong – this is one of the cheesiest movies I’ve ever seen. And there’s a lot of sex. But considering its period, I think it presents some interesting ideas about women. I think it was one of the first comic book action films ever made: interesting that it’s led by a woman considering the attitude towards female-centric action films in Hollywood today.

I agree with Cindy, the fashion link is interesting and absolutely necessary to a movie like Barbarella. I had a funny thought upon realising that Rabanne had done the costumes, because when I think of him, I think sexual liberation and not undermining women into a stereotype. I guess it’s an issue of the gaze, because you have the same person doing a work with two completely different results. But maybe that’s just me!