Florence Lawrence might be one of the screen’s most overlooked silent movie stars, but it certainly wasn’t from lack of trying. During her career, she appeared in almost 300 films; in 1909 alone she starred in 65, many directed by D.W. Griffith. In today’s celebrity-obsessed world it’s impossible to imagine anyone with that level of screen time retaining any kind of anonymity, but Lawrence was playing to a different system, achieving fame at a time when actors weren’t listed or billed, so concerned were studio executives that they’d have to pay their star players more. They wanted it to be about the film (and the profit), not the individual. But of course, when your output is that prolific, public adoration is inevitable. Lawrence’s fans gave her the moniker ‘The Biograph Girl’, a name that would later come to be associated Mary Pickford.

But it’s not just the anonymity that’s impossible to fathom. Lawrence’s entire, ultimately tragic life-story doesn’t sit within the constraints contemporary audiences have for ‘movie stars’. She was attractive and talented, understood the power of publicity and was (extremely) hardworking, but she was also outspoken, vaguely scandalous and had an uncanny ability to never know when she had overstayed her welcome. But that all came much later in her career. Although many of her films have been lost, much of the footage that remains paints her legacy in more flattering shades – vivacious, statuesque and versatile, comfortable in any role (and any situation) the script called for. Blessed with strong features, she was easy to recognise and remember and, although beautiful, she was relatable and engaging. Of course, these weren’t traits that were expected from an actress, Lawrence was a pioneer in a medium that had no context, and had to prove itself as an art form. Success wasn’t guaranteed for anyone – be that screenwriter, director or actor – everyone involved was taking a gamble, and it’s a testament to Lawrence’s love (and single-minded conviction to) for her profession that she made it, only to be rejected by the industry that shaped her.

In many ways, the story of how and why is almost as important as the what. ‘Hollywood’ was a long way from Lawrence’s Ontario origins, and it wasn’t, by all accounts, an easy ride. Her career began just as cinema was born, before there was a movie star success blueprint, before anyone knew how transformative cinema would be. But perhaps Lawrence was made for the screen. She was on-stage from the age of four; after her father left home she regularly took to the stage with her mother, a vaudeville actress who devised ‘Baby Florence, The Kid Wonder’: a (fairly) successful act. According to Kelly R. Brown’s extensive biography, Lawrence ‘learned to wink at her audience the very first time she ever appeared on the stage alone’. Following a nomadic early life, Lawrence’s mother moved the family to New York, where she encouraged her daughter to practice athletic pursuits. Luck or foresight, it was these abilities that landed Lawrence her first movie role: in 1906, aged 20, she was secured a small role in Daniel Boone/Pioneer Days in America, directed by Wallace McCutcheon and Edwin S.Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company. During the one of the outdoor shots, Lawrence was required to ride a spirited horse. Although Lawrence was not enamoured with her performance, the film was a commercial success, convincing the actress that she should seek more work as a motion picture actress.

Lawrence’s ‘big break’ came when career-maker D.W. Griffith gave her a star role in The Girl and the Outlaw (1907). She went on to star in many of his shorts, notably a popular series of Mr and Mrs Jones comedy shorts; matching her popularity with weekly (rather than daily) wages and on-set demands, including her own make-up table. It was during this period that the ‘Biograph girl’ moniker stuck (Griffith was employed by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company). It was turning point for Lawrence: the audience recognition lent credence to her demands, and as she evolved from anonymous to named, she was able to control more of her share. But her demands were not entirely welcomed by the Biograph management, who fired Lawrence in 1910.

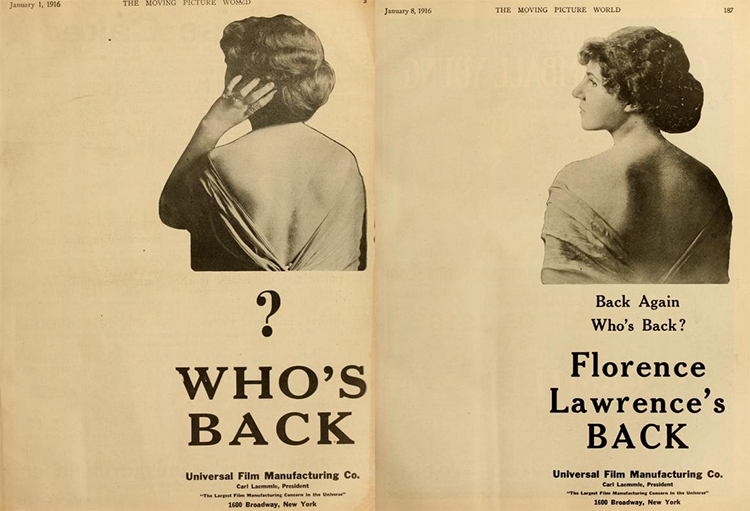

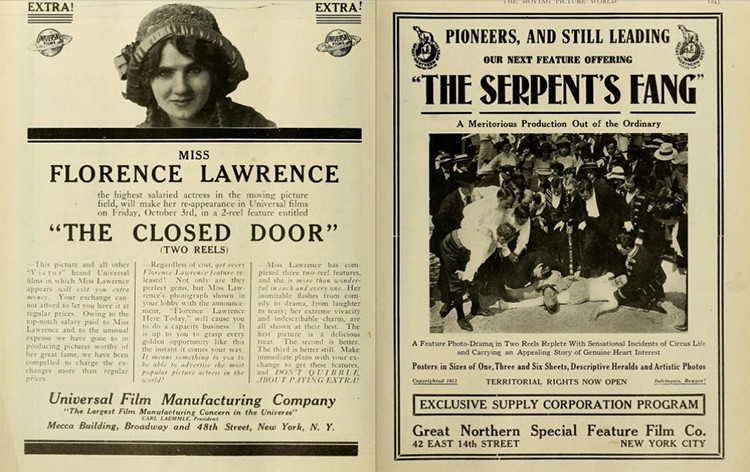

Of course, Lawrence wasn’t out of work for long, swiftly hired by producer Carl Laemmle who capitalised on her public persona to promote his recently-launched Independent Motion Picture Company (IMP). In a prescient stunt, he initiated a nationwide hunt for Lawrence, who – he claimed – had been kidnapped by his competitors. Hysterical headlines ensued, culminating in her ‘death’ in a streetcar accident – only for Lawrence to ‘reappear’ during a promotional screening at a theatre in St. Louis. Almost overnight, everyone knew her (and IMP’s) name.

Lawrence’s fame was a double-edged sword – it allowed her to make salary claims but tied her into a ruthless production machine that didn’t understand its own limitations. Her star billing was a useful tool, but it wasn’t reflected in her influence and position within the company or the filmmaking hierarchy. It looked like that might change in 1912, when Lawrence made a deal with Laemmle, effectively allowing her to form her own company. She was paid $500 a week, an astronomical sum for the era, but the money didn’t translate into measurable success, instead it functioned as a bribe tactic. Lawrence was still at the mercy of the studio, who used and manipulated her image for their profit – in fact she became so popular (read recognisable) that she developed a series of aversion tactics, including escaping from restaurants through kitchens. It’s a long way from pioneer to pawn but Lawrence became increasingly trapped in her own success; her struggles recall Marilyn Monroe’s efforts (some 40 years later) to be seen as something more than the eye-candy. Lawrence might not have been objectified in the same way as Monroe, but she still struggled to shape her career into something that she wanted. And in the heady, early days of cinema, there was no one to turn to for advice.

That wasn’t the end of Lawrence’s misfortunes. Whilst filming Pawns of Destiny in 1914, she injured her back carrying co-star Matt Moore from a burning set building. Laemmale declined to pay for the medical expenses, and the star was forced to undergo a series of botch-job operations and plastic surgery procedures. She returned to work within the year, but collapsed after completing Elusive Isabel, her next film. With Mary Pickford waiting in the wings, Lawrence’s star may have been in decline but the medical complications surely exacerbated the process, leaving her suddenly out of favour with both studio and audience. She retired from screen for eight years but struggled to make a comeback despite her best attempts, which included a nose job (1924). Quite simply, the movies had moved on; in an industry that thrived on the new, faded, former stars weren’t welcome. In the interim years, Lawrence supplanted bit-part roles with a beauty supply store, located just two blocks from the Silent Movie building. She satisfied her entrepreneurial tendencies with a series of inventions (including a vehicle turn signal) that she failed to patent and earn any money from. Perhaps those unclaimed and overlooked inventions sum up Lawrence’s career better than any biography – identifying a need and a gap in the market but failing to capitalise on its full potential.

The final years of Lawrence’s life tell a particularly sorry tale. In the wake of the economic depression, and following her second divorce, Lawrence returned to the screen in the 1930s after MGM initiated a charitable programme that offered bit-part roles to former silent movie stars. Most of these roles were uncredited, but they were paid – usually around $30 a week – a pittance compared to her former contracts, but they provided a link to her former life. According to Brown’s biography, Lawrence retained many of her forthright opinions and ideas, sharing them with the cast and crew of new productions. In 1937 she was diagnosed with a rare and incurable bone disease; the diagnosis cut her life short as a depressed Lawrence committed suicide the next year. According to newspaper reports, her final note communicated ‘they can’t cure me, so let it go at that’.

A tragic end to a pioneer who showed so much early promise and was instrumental in the development of a fledgling industry. Perhaps comparisons with Monroe are obvious, but it’s impossible to ignore certain parallels. Lawrence gave film (and filmmaking) everything she had at a time when success wasn’t equated with fame, fortune and glamour – the industry took everything she had to offer then left her on the shelf despite her attempts to gain control over her own destiny. The drop-and-disregard treatment of Lawrence set a standard for the treatment of women within the movie industry, a standard that included marginalisation and a look-don’t-touch mentality and would take years to break. The ‘first movie star’ epitaph that’s was engraved on her grave in 1991 was too little, too late, but at least it’s an acknowledgement of the contribution she made.

Further reading: Florence Lawrence at the Women Film Pioneers Project / Florence Lawrence, the biograph girl: America’s first movie star by Kelly R. Brown

Wow, what a fascinating and sad story. Thank you so much for giving this woman, and star, the attention she deserves! And in such a compassionate way.

There are so many early film pioneers who don’t get the recognition they deserve. It’s nice to redress the balance even if just a little. It’s a shame so few of Lawrence’s films have been lost.

Such a tragic story, especially considering she had so much promise. When you see her on film (as in the two clips you posted), she is so beautiful and charismatic there was no way she WASN’T going to be a star.

Thank you for joining the blogathon with this thoughtful and well-written look at Florence Lawrence.

She certainly had presence, I guess she was just eclipsed by other early stars (Mary Pickford springs to mind). Am really enjoying this blogathon – have discovered so many gems; thank you for co-hosting!

Very interesting story proving that since the beginning of the movies stars have incredible highs and lows, and that fame is easy come easy go, sadly. I cannot believe the extent to which they’d go for publicity, that kidnapping/return thing is amazing! Thanks for taking part in this event, great to have such a star profiled.

Amazingly Lawrence wasn’t the only actress Laemmle used this stunt on – Ethel Grandin was also a less than willing victim. It’s funny to think how early some Hollywood standards were set in place. Thank you for co-hosting this blogathon, I’ve discovered so many gems!

What an interesting and tragic life. I’ve never heard of her, which now seems such a shame. Thank you for sharing her story.

Thank you for reading – glad you enjoyed the post. There are so many under-repped early film pioneers so it’s nice to play even a small role in redressing the balance.

Incredible highs and lows, and a fascinating life story. Sounds almost like a movie.

GirlsDoFilm, your blog post about Florence Lawrence is fascinating and poignant. Talk about rags to riches and back only to be forgotten! I can certainly agree with your comparison with Marilyn Monroe. Excellent post!

Thank you – so happy you enjoyed reading it. I hesitated about the Monroe reference at first as she’s so well-known I didn’t want her to steal Lawrence’s thunder, but there were just too many parallels for me to ignore!

I agree – although bio-pics hardly ever do the original star any favours so lets hope no-one gets any ideas 😉

Thanks for reading!

Never knew much about Florence Lawrence except what I had read in William Goldman’s “Adventures in the Screen Trade”, and this was a fascinating, informative read. Thanks!

Thank you! That book has been on my wishlist for a while. Would you recommend?

Yes, I would. Don’t always agree with his opinions on things (he seemed to think stars were a greater threat to a movie’s quality than studio executives, and as much as stars have tried to soften a character, or story, so it doesn’t conflict with their “image”, I still maintain he’s off base on that), but it remains an invaluable guide to why the movie business is the way it is.

I knew a bit about Florence, and I know a lot more after reading your post. mIt’s impressive how so many star-exclusive stuff beggined with her: running away from the crazy fans, being recognized worldwide, receiving a small fortune for every movie shot, overworking, being forgotten by the industry that created her (and she heelped create), and suffering from depression. Thanks a lot for such a great post.

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! 🙂

Kisses!

http://www.criticaretro.blogspot.com.br/2014/10/marie-dressler-fatos-rapidos.html

Thanks Le, glad you enjoyed it. I was surprised to discover how much and how quickly the cult of celebrity evolved. It certainly puts the pressures contemporary stars face in a new light!

You know, it’s interesting that as much as I’ve heard about Lawrence (although I haven’t picked up the actual biography on her yet), I can’t recall hearing that she’d been diagnosed with an incurable bone disease. Just can’t remember. With most articles, the implication is that her fall from stardom is what made Lawrence decide to end her own life. She is certainly a tragic figure either way–but dang, these facts matter a great deal!

I also appreciated your comparison with Marilyn Monroe, and the way her unclaimed patents seemed to symbolize the outcome of her career–nice insights.

Thanks. I’m a big Monroe fan and something just struck me about the two of them. I guess they’re not the only actresses that have been used and exploited but for these two it really does feel like a tragedy – perhaps because of the path their life took.

I do recommend reading Brown’s bio if you want more Lawrence, I only skimmed through it for the post but it seems very thorough: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Florence-Lawrence-Biograph-Girl-Americas/dp/0786430893

I always love to read about forgotten stars. If someone is writing about them today I like to think they are not completely forgotten.