Belle de Jour “was my biggest commercial success, which I attribute more to the marvellous whores than to my direction” (Luis Buñuel)

There are very few films that effectively examine female erotic fantasies (coming-of-age sexuality tales, on the other hand, are a different story). Belle de Jour – Luis Buñuel’s exploration of one woman’s inner fantasies and desires – is far from perfect but, almost 50 years after its release, it remains one of the best-known erotic films, thanks in no small part to Catherine Deneuve’s cool, unassuming performance, which is the perfect blank canvas for debauchery. More than any other film from the actresses’ first decade, the role defined the ‘Deneuve’ persona: a blank slate onto which audience and filmmaker’s fantasies could be projected.

Yet Deneuve’s poised exterior masked turmoil. Filming encompassed everything from nudity to flogging and being pelted with muck, and in a 2004 interview with Pascal Bonitzer she observed: They showed more of me than they said they were going to … There were moments when I felt totally used”. That showing doesn’t just refer to the flesh (Deneuve was reportedly unhappy with that, although in retrospect there’s perhaps not as much nudity as you’d expect in an ‘erotic film’). This is about a character laying herself – and her fantasies – bare. Doing things that both the audience and the character doesn’t expect.

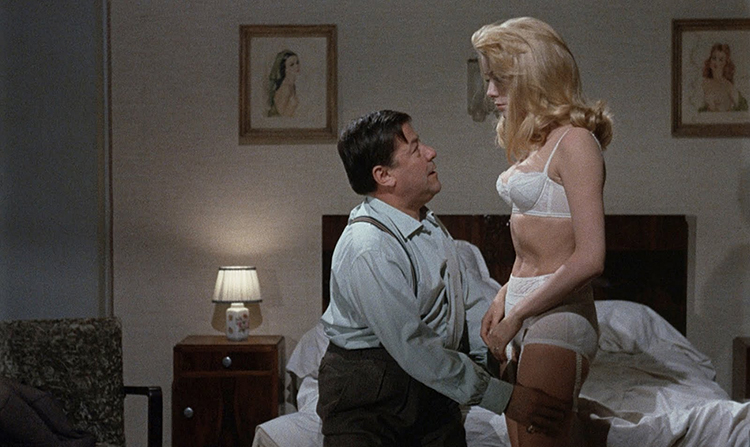

Based on a novel by Joseph Kessel, the film charts the sexual awakening of Séverine (Deneuve), a refined-but-bored Parisian housewife who spends her afternoons working in a brothel. Unlike her co-workers, she’s not there for the money. She’s there to learn something about herself and better understand her repressed desires which, as the audience learns from the opening scene, border on masochistic. For Séverine, the gulf between fantasy and reality is vast. She fetishes torture, kidnap, whipping. She wants to control pleasure and pain – both her own and that of her partners. In reality, she and her surgeon husband sleep in separate (single) beds, wearing practical night garments.

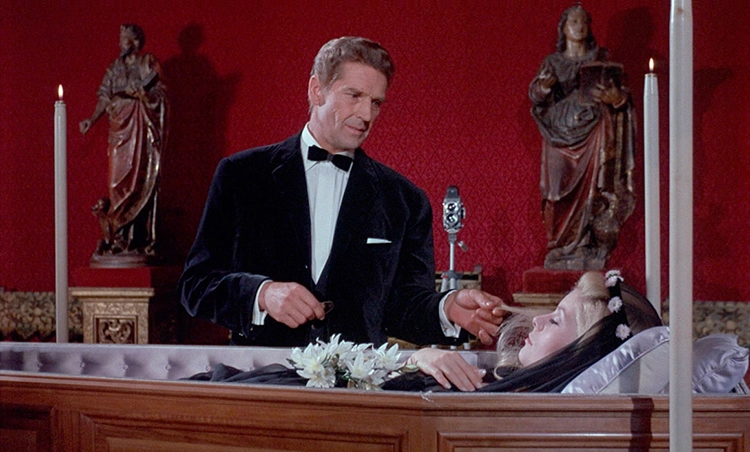

Buñuel deals with eroticism from the inside out – Belle de Jour is less about the physical manifestation of desire, more about how it exists in the mind and how those imagined fantasies can blur with reality. Much of the film deals with the dichotomy between ‘truth’ and ‘fantasy’. Consider again that startling opening scene – what we first take to be real and shocking is actually imagined. Yet later, after Séverine starts working at Madame Anais’ discreet brothel, the coach from her fantasies appears in real life, and whisks her away to a country manor where she is required to entertain a local Duke (Georges Marchal) by posing as his dead daughter and lying in a coffin. Is the experience real? Or imagined? In the end, it doesn’t really matter – it’s whatever the viewer needs it to be. Similarly, the small lacquered box that a client brings to the brothel. The first girl is disturbed by its contents. Séverine is initially cautious, but the scene cuts away – deliberately ambiguous. It’s impossible to discern what exactly happened. Of course, what’s in the box is of little consequence. Buñuel cares only about the symbolic truth.

Although Buñuel was famously resistant to psychological interpretations of his films and the characters he created, there’s a ring of authenticity to Belle de Jour. In fact, real women inspired all of Séverine’s fantasies. During production, the director and his co-writer Jean-Claude Carrière met with psychiatrists, prostitutes and brothel owners to discover female fantasies and how they manifested in the everyday. Perhaps aware that an all-male production team created the movie, it was important to root the movie in real stories. As a result much of the narrative, which appears to be real, is fake. It’s the fantasies that are true. As with much of the film, ‘truth’ is nothing more than a deception.

Belle de Jour might chart Séverine’s sexual awakening, but she remains an enigma. Short montages (a brief glimpse of her being molested, a communion refusal) may hint at the root, but the truth is never revealed. Why do her husband’s advances repel her, yet gangster Marcel (Pierre Clémenti) swagger attract her? On his first brothel visit, she tells him: “for you, there is no charge”. His metallic teeth, leather jacket, swordstick and arrogant swagger are far removed from her refined, bourgeois world. They embark on an ill-advised affair with tragic consequences, but its Séverine’s attraction to what he represents that allows her to risk everything she has. Really he’s nothing more than a prop, one that’s able to corrupt her vision of who she is simply because he is her opposite.

Most, perhaps all, of Séverine’s fantasies put her in the centre, and although she is never exploited, neither is she fully empowered. At the film’s close, the audience isn’t exactly sure what will become of her. She is both vamp and victim; one that pays a cruel price to uncover something that existed beneath the surface. What’s pleasurable might deviate from the socially-accepted norm, but there’s a price to pay for discovering it. And of course, because her liberation is obtained via submission and humility, it’s easy to argue that the film is in fact repressive. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. Or perhaps we should take Buñuel’s lead and allow it to be whatever we need it to be.

Some notes on the costume

One of the most important facets of Séverine’s inscrutability is her impeccable, elegant wardrobe, designed by Yves Saint Laurent. Reports suggest that Buñuel and Saint Laurent had a tough job convincing Deneuve not to wear short skirts in the movie in a time when mini-skirts were in fashion, but the decision certainly worked in the film’s favour – it remains one of the most iconic looks in celluloid history.

Séverine’s wardrobe works on two levels: the smart military details (double breasted closures and epaulettes) allow her to present a smart façade to Parisian society, but also represent the structure and rigour that she exerts on her own lief. Luxurious fabrics (fur) and unexpected textures (vinyl and leather) hint at her ‘dark side’ but are also perfectly in tune with the bourgeois. Her contradictory nature plays out in the garments she wears. It’s testament to Laurent’s talent though that although the clothes are undeniably beautiful and perfectly constructed they never overtake the scene or the character – Séverine might not be fully in touch with who she is, but she knows how to present the impression of control.

See Clothes On Film and Glamamor for a more comprehensive analysis of Yves Saint Laurent’s costumes.

This post is part of the France on Film blogathon, hosted by the wonderful Serendipitous Anachronisms. Catch up on all the posts here.

A wonderful review. What an interesting concept by Buñuel and I appreciate your analysis of her costumes. As a character “she is never exploited, neither is she fully empowered” suggests a weakness in the script in that it would be more interesting had she gone one way or the other. Does the ambiguity add to the film or detract?

Thanks Cindy! I think the reason why I can’t pin down exactly how I feel about Séverine is partly because of Buñuel. The ending is so ambiguous and references her fantasies, but as a viewer you’re not exactly sure if she will now live happily or if she’ll still remain repressed. When you’re watching the film it feels like a natural conclusion, but post-watch it’s something of a let-down!

Wonderful review. So detailed and thorough. I have an affinity for movie costumes and the people who make them. Big thumbs up here . . .

Glad you enjoyed it – thank you so much for reading and commenting!

This made me think alot. Insightful stuff 🙂

Thank you for reading! So much has been written about this film it was hard to know where to start!

Thank you for your contribution to the France on Film Blogathon, this is an excellent post. You really dug deep into this film and offered an enlightening information on Bunuel’s perspective.

Being a costume lover and vintage clothing lover, I especially loved your observations on the costuming, because when we want to “dress French”, we always use this film as an archetype.

I felt so sorry for Catherine Deneuve knowing she felt used by this film, that is unfortunate.

Thanks for such a great read!

Thank you for having me 🙂

I felt quite sorry for Catherine Deneuve too, until I realised that she went back for more a few years later in Buñuel’s Tristana, in that she loses her virtue and a leg!

This is one that I’ve been meaning to watch for a long time. I like the way you highlighted how the film’s ambiguity lends it symbolic power but also renders Séverine something of an ambivalent character.

I thoroughly enjoyed this pictorial presentation! It’s an often misunderstood film that’s worth coming back to.

Great article, as always! I’ve seen Belle de Jour some years ago, and it is not very fresh in my memory. But I agree it’s an open film. You can’t find only one meaning for everything Buñuel shows or rather suggests. It changes from viewer to viewer!

Thanks for the kind comment!

Kisses!

Le

I watched this film several years ago when a former student was in college taking a course on gender roles. She needed a recommendation of a foreign film that presented a woman in a non-traditional role. I never could decide if this fit. I wish your analysis had been around then. I think you really hit it. Deneuve’s character is both in a typically female role in that she is being exploited somewhat, but because she chooses the life, she is also empowered. The costuming enhances this idea, as its elegance is in such sharp contrast with her time in the brothel. (And, of course, it is timeless!)

The blankness on Séverine’s fact that you point out is so important. I always felt that this helped the audience to identify with her.

Thank you for this thought provoking piece on one of my favorite pictures, one I have seen dozens of times over the years without having arrived at a concrete interpretation. I tend to side with Bunuel’s opinion of Denueve as an actress of weak intelligence, and perhaps it is this mask of elegant stupidity that so befuddles an audience that wants to read something into her. Men who chase beauty expect to find something behind the beauty, but instead are confronted with the uselessness of beauty. Denueve’s Severine provides perhaps the cinema’s most extreme investigation into the “male gaze.” The poster, which hailed it as “Luis Bunuel’s Masterpiece of Erotica,” boasted a naked-from-the-small-of-the-back-up portrait of Catherine Denueve, No guy could look at that poster and not get a craving to see the movie. And when I saw it, it was a case of non-consensual sex imposed upon an emulsified vision of light by a horny sixteen year old kid.

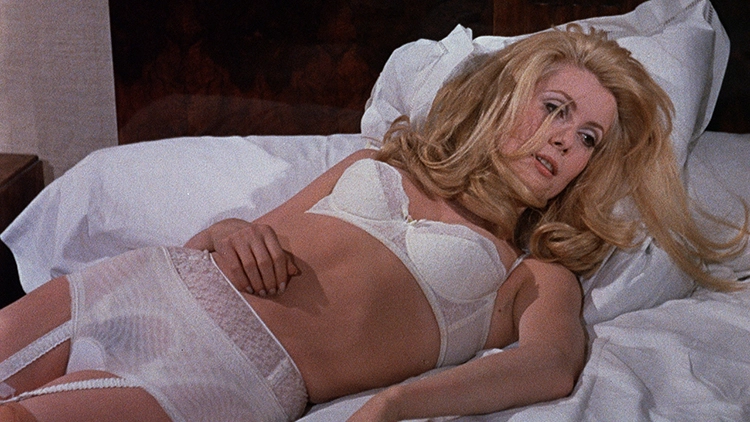

“Belle de Jour” was Catherine Denueve in bra, panties, and garter belt with nylon stockings, Catherine Denueve sprawled across the bed on her belly, a satisfied smile buried beneath blonde hair, Catherine Denueve tasting the whip while tied to a tree, Catherine Denueve’s knees and the promise of leg, Catherine Denueve’s rear view nudity that shows absolutely nothing but gives you the feel of her all naked in your arms, Catherine Denueve in a coffin with something vibrating beneath her, Catherine Denueve kissing, being kissed, a proffered kiss rebuffed, and Catherine Denueve removing her bra, panties, garter belt, and nylon stockings.

Luis Bunuel slurs this beautiful woman with mud and gives her to the chauffeur to do with what he will, then gives her to all of us who go to the cinema by day. I am Pierre Clementi, and will never be as good looking as her husband, but I will possess her and he will not possess her. We who are Pierre Clementi have fetishized the last drop of sex out of her. She is our collective dream of sex but there is no sex left in her. She exists only for the gazing. The film exists only for her. We exist only for the film, to watch the film. The film is a gang rape by the collective eye, and each rapist sees himself as the film’s true lover.

“Belle de Jour” is a catalyst for sexual desire without the messiness, without even the visual messiness, of sex. As such, it is the purest experience of pornography yet offered by the cinema. We are not projecting ourselves into the sexual acts of others, but eliminating the sexual act itself from the idea, or the ideal, of the sexual act. But such idealization can be fulfilled only by defiling the erotic pose, never by merging with it. That is the ultimate end of every fetish. But Bunuel spares his viewer the violence of resolution by awakening him without interrupting the dream.