This post is my contribution to the Great Movie Debate blogathon, hosted by The Cinematic Packrat and Citizen Screenings. Check out all the great entries here, especially Movie Movie Blog Blog who’s taken the FOR argument for Citizen Kane.

When it comes to Citizen Kane, the ‘against’ corner is a pretty lonely place to be. The movie, voted ‘the best of all time’ by Sight and Sound readers for more than 50 years, is an undisputed cinematic great, but its greatness is thrust upon it and comes most from it’s lasting influence rather than from the movie’s intrinsic value. It’s a movie you feel compelled to like – any other response signifies a lack of cultural understanding or an inability to ‘get’ greatness. But surely that’s not what movie watching is about – the thrill is in the immersion, in the experience, in the act of being swept up into another life or place – and on those counts, Orson Welles’ so-called masterpiece fails.

So with no further ado, I present the prosecution’s case…

The plot. Or lack therof.

Five writers (three uncredited) could surely have constructed a more compelling narrative. The autobiographical framework – told post-humously through a journalist who’s attempting to uncover the meaning of Kane’s last words – results in uneasy neutrality that makes it difficult to emphasise with any character. Much of the blame should be attributed to Welles and Mankiewicz, who were the lead writers. Although it was Welles’ first full screenplay, by the 1940s, Mankiewicz had been writing and adapting for more than 10 years (credits included Dinner at Eight, Ladies’ Man and Dancers in the Dark). Surely he could have constructed a more compelling narrative and richer dialogue – compare the just-about-average exchanges with The Maltese Falcon and The Lady Eve – both released in the same year as Citizen Kane. Quotable lines from both abound – the most memorable line of dialogue comes from Leland (Joseph Cotten) ‘ I can remember everything. That’s my curse, young man. It’s the greatest curse that’s ever been inflicted on the human race: memory.’ How the film won an Academy Award for Best Writing will forever remain one of life’s mysteries.

The blame does not rest entirely with Mankiewicz: Welles should have demanded repetitious scenes be cut and replaced with supplementary ones. The flashback technique is only unsuccessful because it’s too languid and indulgent. The lack of plot development is also problematic. The conclusion – which remains the audience’s secret – is presented as meaningful and profound but in reality falls flat. It’s not enough of a ‘reveal’ to build up to and, as Dan Geddes observes, although it makes the point that the meaning of a man’s life cannot be discerned from his dying words, the point could have been made earlier and the film could have been resolved more satisfactorily.

Kane is one-dimensional.

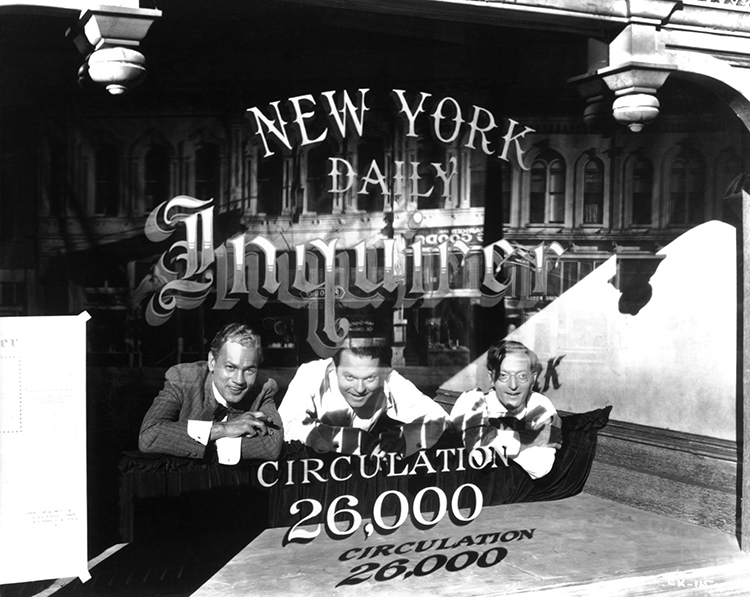

At his heart, Kane is overly ambitious man with political aspirations. Although apparently a pastiche of real-life characters, including publisher William Randolph Hearst, tycoon Howard Hughes and Depression-hit entrepreneur Samuel Insull who built an opera house for his wife, Kane doesn’t feel particularly individual. In fact he’s not actually likeable – that in itself isn’t a deal breaker, but it’s impossible to care for a character that doesn’t seem real, for whom nothing really feels at stake. The audience isn’t emotionally invested enough to care what happens – Kane is distanced by his money and by the other characters, who all help to create a myth that is never shattered. The ‘Rosebud’ realisation comes to late to humanise his actions, to redeem his selfish, ruthless and selfish actions, and his ability to destroy the lives of those he claims to love. Everyone has faults – Kane’s aren’t sufficiently unique enough to make him interesting – and his character is painted in broad, ‘big-picture’ brushstrokes that overlook the small details and, in doing so, render him almost inhuman. In fact, the more the audience learns about Kane, the more he recedes from view.

One of the most dramatic (and therefore engaging) scenes is when the Governor of New York Jim Gettys (Ray Collins) corners Kane, his wife Mary (Ruth Warrick) and his mistress Susan (Dorothy Comingore) in the same room. Gettys threatens to expose the ambitious Kane unless he halts his corrupt political campaign. Kane chooses his mistress over ‘family’, but that relatability is undercut by the fact that no mention is ever made of Mary again – despite the fact that the opening news sequence reveals that his wife and son were killed in a car crash soon after the confrontation. A reference to Kane’s grief (or lack of) would immediately explain or justify further actions – ignoring it only makes him more unrelatable – whilst also making the screenplay that little bit more annoying.

The techniques are distracting.

They’re not distracting when you’re watching it, but they’re distracting on reflection – the pleasure of a post-watch consideration is considerably lessened by the realisation that not a lot actually happens and much of the film is carried by Welles’ (undeniably brilliant) camerawork and ideas. Stylistically Citizen Kane is an early example of film noir, but these darkly atmospheric shots create an illusion of mystery that plot and characterisation fail to live up to. Of course, it’s not exactly a noir: Kane’s fate is bleak but is firmly in his hands – he is the master of his own destiny.

There are many stylistic elements that make Kane great – the unexpected camera angles and the use of deep focus (notably in the scene where a young Kane is playing in the snow-covered garden in the background whilst his mother signs over the legal rights to her son). Roger Ebert even claimed that there are more special effects in Citizen Kane than there are in the original Star Wars film, and he’s probably not wrong. But a film is the sum of its parts, and these areas of excellence are not enough to make up for the shortcomings that have already been mentioned.

Oversell – the false promises of universal acclaim.

For current audiences, Citizen Kane has been oversold. It’s a textbook example of a myth that’s grown too big to be sustained, and is a touted must-see for all the wrong reasons. There’s no question that, with Kane, the young Welles (just 25 years old!) made an undeniably influential film that changed cinema and ticks almost all the ‘film as art’ boxes (inventive, auteur vision, an enduring moral) – but textbook examples don’t make a classic. That status comes from the experience, the pleasure and the joy – all of which Citizen Kane lacks in spades.

Further reading: Citizen Kane by Erich von Stroheim / Citizen Kane: Not the greatest movie ever by Dan Geddes / Praising ‘Kane’ in The New Yorker / Raising Kane by Pauline Kael / Citizen Kane by A Movie A Week

Great post! I am a fan of Citizen Kane but I think you made some very insightful points, especially about Kane as an unsympathetic, almost inhuman character. I was struck by your observation that the more we learn about Kane, the less real he becomes.

Citizen Kane is truly a “Look at me, how clever I am with a camera!” film, which makes me roll my eyes at times, but I still love his techniques. I’m a sucker for an unusual camera angle.

P.S. My husband would COMPLETELY agree with you about everything you’ve said. He thinks Citizen Kane is one of the most overrated movies from classic Hollywood.

I do understand why it’s beloved – it feels epic as you watch it – but for me, ultimately, it’s not something that stays with me, there’s nothing profound. My favourite Welles film is The Third Man – as a man of good taste I’d be interested to hear what he had to say about that!

BRAVO!! While I enjoy KANE for memorable shots throughout the film, I agree with most of your notations and applaud you taking on the difficult task of – OH MY GOD – dissing KANE!!! I did a post last year defending HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY and its deserved Oscar win over KANE because it drives me crazy that people think that win was out of left field, etc. While I enjoy KANE I too find it distracting with Welles’ an overindulged presence. Great read and post and I couldn’t be happier you did this. FANTASTIC!

Aurora

I disagree entirely (and BTW, Kane’s estranged wife was played by Ruth Warrick; Agnes Moorehead played Kane’s mother). But other than that, your criticism was spot-on and delightful to read. I don’t mind disagreeing, I just mind being bored. Your review was excellent reading!

Good spot – thank you! I’ve let the prosecution down. I’m happy for you to disagree, I’m fully aware I’m in the minority here, but sometimes it’s refreshing to air what you REALLY think about something…right?! 😉

I’ll have to read that post – sometimes it’s good to be controversial and take the opposing view. Welles was so young when he made this, he must’ve been keen to make it his and exert his stamp on filmmaking. Too much auteur isn’t necessarily a good thing! This has been such a fun (if divisive!) blogathon!

Salient points, all. Yes, it is a brave stance you took, but you´ve organized a good case!

I was quite apprehensive about posting my view as I know I’m not in the popular camp – but all’s fair in film and debate, right? Thank you for reading!

Wow, what a great lawyer you were in this case!

I think that Kane is only surprising and thrilling in the first viewing: later you get distracted by th camera techniques because you no longer need to find out what (or who) is Rosebud. When I saw it, I already knew the meaning of Rosebud, so it was a mystery less to me. And I totally agree that Kane is not likeable. And this is definetely not the first film with flashbacks.

Really, what makes Kane good is th innovative camera work. For me, Welles’ best film is The Lady from Shanghai.

Thanks for your comments, always!

Kisses!

Now I MUCH prefer The Lady from Shanghai. Perhaps I’m too contrary to like what I’m ‘supposed’ to, but in my (humble!) opinion Lady is a far superior film – brash but dreamlike, and such incredible chemistry.

Weeelllll…..You make some good points. I do agree that Kane gained a rep that was quite a bit out of proportion to it’s quality. It’s the Muhammad Ali of movies – it is long past the point where people step back and look at it with fresh eyes. I agree that Kane’s character isn’t illuminated as well as it could be.

I am delighted that you bring up the point of the death of the son and wife. I watched it again a few months ago, and that point jumped out at me….,Why does the film mention the death of the son and wife in the newsreel, and then not refer to it again?

I still admire CK, but it is mainly for itS technical brilliance – I still think it is a seminal film in terms of narrative structure, cinematography, lighting, and sound.

Nice commentary – Your writing is always a delight.

Thank you for your kind comment. The Ali analogy is spot on, and as Le commented above, perhaps much of the power is lost after the first viewing. A mention of his wife and son’s death would have humanised Kane immeasurably – and for me would have made him a better character. I’d like to think Welles cut it out, but he left so many other unnecessary scenes in that I find that rationalisation unlikely!

Thank you for expressing what I’ve always felt about Kane. In fact, you’re much kinder to it than I would be given that it (a)succeeded in convincing my sister she was right not to give classic films a try and (b) almost did the same to me. I feel like Sight and Sound does what no best-of music list–or even best-of book list–would do: completely disregards likely popular sentiment. I doubt that any best-of music list, for example, would pick a song for number one only musicians and historians could appreciate, yet here Sight and Sound is: teaching generations of hesitant classic film viewers that they have to be into camera angles to appreciate the best film of all time. And we wonder why so many people think classic film is inaccessible. I’m just lucky after my “Huh?” reaction at sixteen, I picked something better.:) Leah

Quite a gutsy choice of film for an “against” argument! Thoughtfully done, and you lay out a good case for why this film could be considered overrated. Or, why many savvy movie fans just aren’t sold by all the hype.

I will admit that I’m in the “for” camp. I would argue that Kane’s seeming one-dimensional quality could very well be deliberate, and that it fits what the film was going for. He is perhaps the most vivid as a child and as a young man in the beginning of the film. By the end he has progressed to becoming a remote Public Figure. His power and wealth are beyond imagining–the shots of the massive Xanadu not only make the estate seem remote and unreal (as do the matte paintings of it), but the newsreel narrator in the beginning gives it an added “impersonal” touch. Charles Foster Kane, in a sense, evolves from being the more human Charles and to being the wealthy and immensely powerful KANE (in those big letters!). Those shots where his figure is seen as towering in the foreground, with the characters looking at him in the background, reinforce that idea.

Those, of course, would be my own thoughts on the character. But your criticism of Citizen Kane is what made me look at that aspect in a new light and examine it closer–which is exactly what good criticism should do.

You’re not alone. I feel the same about Kane, its lack-lustre as a film from a plot point of view, technically I can see its power, but without the plot how has it earned such high regard?